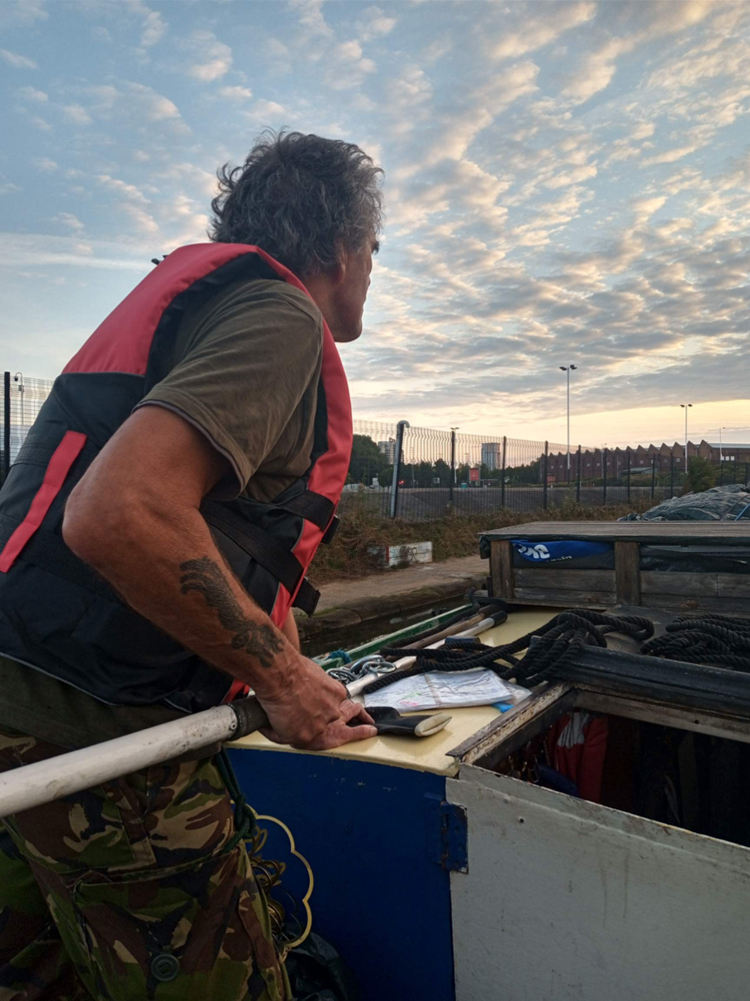

Nick Ford

Nick Ford is an historical writer with a lifelong interest in the paranormal, folklore and the timeless romance of waterways. Educated at Lancaster University and the University of Southampton, with an Honours degree from the Open University, he spent 13 years working for the Royal Navy, the best years of which involved messing about in boats and getting paid for it.

Nick’s previously published books are a history of Jerusalem at the time of the First Crusade, a biography of King Henry VIII and a re-evaluation of the life and work of the much-misunderstood Renaissance genius Nicolo Machiavelli.

In Canal Ghosts And Water-Wights, Nick combines his academic interest with a spirit of open-minded enquiry into why so many strange phenomena have been reported on the waterways of Britain over the centuries, with a sometimes light hearted but not irreverent touch and, as someone who has taken part in number of private psychic investigations, offers a variety of possible explanations that include his own experiences as well as those of people he knows – bringing the wealth of folk traditions, legends and historically recorded events right up to some that occurred as recently as last year.

He lives in Ludlow, Shropshire within easy reach of River Severn, the Shropshire Union, the Llangollen, and the Montgomery Canals, and writes a monthly history column for the local magazine.

To read the latest review of Canal Ghosts & Water-Wights from the Spring quarterly issue of Northern Earth magazine ~ Click Here

Nick reads from Canal Ghosts & Water-Wights

Water and the Living Dead

From the beginning, waterways were natural boundaries: places you didn’t go beyond – not if you wanted to remain in your own world; but if you followed a watercourse for long enough, you would, in time, still reach a different world. The water, too, is itself another world, reflecting our own like a mirror, and where different rules apply. Respectful negotiation is needed or, having once entered that otherworld with the wrong attitude, you don’t come back.

As soon as people learned to float on logs, then build rafts and boats, these waterways became highways for trade,

often safer than forest trackways where predators, human or animal, might lurk. But the river itself was a living thing, a composite of many small lives (as are we), capable of doing much harm as well as good. Any entity that can be apparently malign or benign at a whim, calls for a special way of addressing it, a code of behaviour informed by a set of beliefs, and so to all intents and purposes, that entity is a god.

The Celtic inhabitants of Britain are known to have addressed their gods, spirits and ancestors of the Otherworld, with prayers written backwards, in mirror-image writing, on tablets of lead, rolled up into scrolls, and cast into bodies of water. Offerings of jewellery and weapons, all ritually ‘killed’ by bending, have also been found in great numbers. Even today, people seem to have some kind of inbred urge to drop coins into bodies of water, especially where others have evidently done so before, as if in a place where prayer has been known to be valid.

Much folklore treats with the belief that spirits – especially those of the dead – cannot cross water, and many therefore are assumed to haunt its banks or inhabit the water itself. In the Middle Ages, many bridges leading in and out of towns included a chapel, as a place where prayer and sacrifice could be made by the traveller as being, in more senses than one, between two worlds – civilisation and wilderness, Heaven and Earth, Earth and Water, the known and the unknown.

As human capability to change the environment grew, rivers were deepened, their meanders straightened and, with the coming of the Age of Iron, rivers were even created: canals. Though a few in Britain were made by the Romans, the vast majority of our canals were created in the century between 1750 and 1850, the age of the Industrial Revolution and what its founding fathers smugly called The Age Of Reason. But though all they may have intended was to make money, to market their goods more profitably over a reliable national transport network – a far greater, unintended achievement lives on, long after their canal network outlived its commercial usefulness: they created a hundred new rivers, each with their own lore and magic and mystery.

The people – the ordinary people – who made the canals, and those who crewed the boats that plied them – did not have the dubious privilege of what was thought to be a rational, scientific education. Most were former agricultural labourers, and many of those were from Ireland, Scotland, and rural Wales, where the old folk memory of ghosts and nature spirits was still strong – and if you believe that something exists, you are far more likely to experience it, than if you don’t.

These are the people who experienced the living waterways in their daily lives, and who often died on them, in them, or beside them. Their stories of the weird and wonderful are still told, and along with their legends the newcomers, the recreational boaters and the liveaboards, have added their own. All their stories I have been able to gather are in this book, which is dedicated to every one of them.